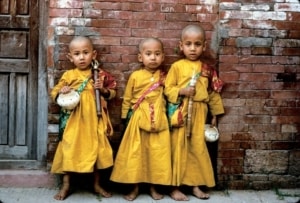

Photo © Michael Rosenkrantz

I’m experiencing something that I never have before; living in a village, not necessarily how most people live, because I’m living in the hostel of a hospital with A/C in my bedroom, although with cement floors in my bedroom, but nevertheless I’m living in a village. Karjanha lies in the Terai region of Nepal not too far from the border of India and the State of Bihar.

To a large extent this is a very traditional village; the women all wear saris, the men seem to be very much in control, people use oxen to plow and ride bicycles (and motorcycles) to get around, there are goats galore, agriculture is the main source of employment, there are tenant farmers paying 50% of their crops to the landlords, there is some English spoken, although many want to learn, the school buildings are in a sad state, there are health issues such as open defecation, urinary tract infections because there really isn’t enough good water to drink, respiratory problems due to cooking with wood in enclosed areas, women suffer from prolapsed uterus, people use hand pumps and bathe in polluted water with their buffaloes and everybody eats daal bhaat two times every day. People shop at the local haat bazaar (market) two times/week, women balancing huge bags on their heads while they walk home and spend hours talking with their families and neighbors, relationships running deep.

The children in Karjanha, like most children throughout the world, but especially in Nepal, are bright eyed and beautiful; they follow me around the market, wanting to talk and try out what limited English they know (which is at times, more than my knowledge of Nepali) but some being somewhat shy of a bideshi (westerner), having never seen a westerner before. I smile at the children and talk to them in Nepali, sometimes they reply, sometimes they just stare, but this makes these children so endearing. Others want to learn English, curious about the outside world. And I want to teach them about this entirely alien world, so incredibly different than what they’ve grown up in.

Riding on the back of a new friend’s motorcycle over the narrow roads surrounded by fields of green, people with their beasts of burden is yes, to me, a person who has grown up in the US, a romantic adventure. But I know that living in poverty is not idyllic. People ask me what am I doing in this Village, not in a mean spirited way, but this question gives me pangs in my belly.

After all what am I, a privileged American, doing in this Village with the heat and insects, living with amphibians (and big frog poops) in my flat and power cuts, hanging my clothes on the roof top in order to dry, finding them scattered everywhere after a bit of wind, having to light a stove powered by a gas cylinder? Really, what is the point? Or as my mother asked me when I was visiting the States, “why do you want to live with poor people?”

After I had arrived back in Nepal, my good friend and cousin Mark wrote me an e-mail saying you are really pushing your limits. I hadn’t really thought about this as it felt quite natural just to come back to Nepal. But in some sense I am pushing to be adventurous, to see what I have deep down, spirit, energy, life.

Living in a village brings up remarkable contrasts. I borrowed a bicycle today and rode (for the first time in who knows how long) on a dirt road seeing women in brightly colored saris returning from the market with bags on their heads; I saw a woman in a pond with her buffalo; I stopped and chatted with children who were wide eyed when they saw me and excited when I brought out my camera and took their photos. Riding the bicycle, I smiled both outwardly– and inwardly as I looked around with happiness reverberating throughout my entire body. Although I’ve seen these sites before in both India and Nepal, I was only visiting villages and not living in one.

There will be an interview with Michael Rosenkrantz on this blog in the near future.